In:

The following is an advance reading for the Members Weekend 2016 panel discussion Global Economic Forecast: Prospects for Growth, Innovation, and Development.

____________________

We live in interesting times. A major American political party has nominated a flamboyant reality star and provocateur for president. UK voters have stood athwart history and yelled "Leave!" Radical jihadists have adopted social media and modern weaponry in a brutal campaign to return us to the Dark Ages. And a long-simmering brew of nationalism, isolationism, and xenophobia has begun to boil over into the mainstream in country after country within the shrinking zone of Western-democratic consensus. Although skepticism of globalization (and all it entails, including immigration, offshoring, and liberal trade) isn’t monolithic, one thing is clear: much of that skepticism in rich countries is rooted in the insecurity of workers at home.

And why not? Workers in poorer countries are (for now) willing to work for lower wages and in worse conditions than their counterparts in richer countries. Similarly, immigrant labor often costs employers less than "native" labor — although the hope and expectation is that conditions for immigrant workers meet at least the same minimal standards as elsewhere in a given country. Starker still, automation may represent an insensate and inexorable march away from workers altogether and toward a potential future of permanently expanded structural unemployment. Under the circumstances, workers aren’t being paranoid for feeling threatened by competition and, eventually, irrelevance.

Given the gravity of this threat and industry’s relentless efforts to squeeze more value from less labor, many pro-worker advocates have called for open revolt against a neoliberal order fueled in part by easy access to offshore or immigrant workers.

Welcome to Luddism.

As a refresher, Luddites were the original "technophobes." Colloquially, a Luddite is someone who doesn’t use email or who is uncomfortable with technology. It’s a snide epithet for people who aren’t good with gadgets. Think of the grandparent who couldn’t program a VCR (back when that was a relevant technological and cultural reference). Luddism is sometimes even caricatured as a kind of primitive Frankenstein complex.

But the historical Luddite was something else entirely.

In the early 19th century, the comfortable security of skilled English textile workers was rocked by the introduction of mechanical weaving frames and other technological advancements in manufacturing. These innovations posed a serious threat to a previously well-insulated trade by "outsourcing" human work to machines.

Equally alarming, machinery in the manufacturing sector meant skilled craftsmen could be replaced with unskilled (and worse paid) operators of the new machines — even children.

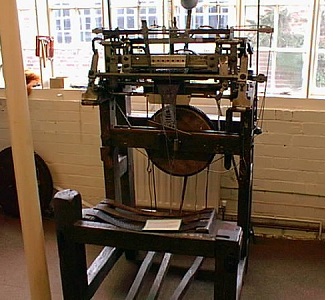

The craftsmen didn’t take these looming threats lying down. In a moment now imbued with the halo of legend, a weaver named Ned Ludd allegedly destroyed two stocking-knitting frames (pictured here) during a fit of fury. Never mind that Ludd, if he existed, was probably actually responding to rough treatment by his employer, or to japes from juvenile bullies. What mattered wasn’t the motive — or even the verifiable existence — of Ned Ludd. What mattered was that the machines were the problem, and Ludd had, it seemed, taken the fight to the machines.

The craftsmen didn’t take these looming threats lying down. In a moment now imbued with the halo of legend, a weaver named Ned Ludd allegedly destroyed two stocking-knitting frames (pictured here) during a fit of fury. Never mind that Ludd, if he existed, was probably actually responding to rough treatment by his employer, or to japes from juvenile bullies. What mattered wasn’t the motive — or even the verifiable existence — of Ned Ludd. What mattered was that the machines were the problem, and Ludd had, it seemed, taken the fight to the machines.

They called him Captain Ludd or General Ludd. To some, he was even King Ludd. A folk hero was born.

The Luddites raged against the machines for years, their revolt eventually culminating in a full-blown armed political uprising. The army ultimately crushed the quirky rebellion, and the movement withered. The Crown demanded repayment from many Luddites with transport and penal servitude. Others paid their royal debt to the hangman.

And for what?

The Luddites’ basic premises turned out to be wrong. Granted, weaving machines did bring many unskilled workers into the labor market. But the advent of mechanized manufacturing actually created more jobs than it cost. And expanded workforce participation increased economic growth and improved standards of living.

But that doesn’t mean Luddites were crazy to fear the transition. The mechanization of industry displaced and hurt many. Not coincidentally, the Luddite riots and uprising also took place at a time of inflating bread prices, with rebels capturing bread and grain even as they destroyed industrial capital. In other words, beyond job displacement, workers were literally starving. But we don’t remember the Luddites for their lack of bread. We remember them for wanting to burn the system down. We remember them for trying to slam the brakes on progress.

In short, the Luddites were spurred by a real problem but lacked thoughtful, effective prescriptions that anticipated the historical changes underway.

Fast forward to a world the Luddites could scarcely have imagined. Despite the jarring differences between 19th century northern England and today’s global economy, technology continues to challenge skilled labor with displacement and dislocation.

Like the Luddites, contemporary workers see a real problem, and they feel it where it hurts. But our prescriptions need not be as memorably hysterical.

Over the last several decades, workers around the world have been lifted out of poverty at an unprecedented rate, in part because of liberal trade.

And when it comes to automation, they aren’t. For instance, Bernie Sanders, whose campaign in many ways channeled the voice of modern American labor insecurity, has publicly entertained the idea of a universal basic income as a means of addressing the displacement caused by automation — and this despite the fact that automation now may be fundamentally different from any precedent in that it might eliminate more jobs than it creates. (And then again, it might not). His campaign would have been written off as foolish if he’d instead called for regulations against machinery or penalties for companies that automate.

Yet when insecurity in the labor market stems from the influx of immigrant workers, or from the outflow of manual jobs to less expensive markets, the prescriptions change. Concerned politicians go from proposing creative and progressive domestic reforms to demanding tighter borders and higher barriers to trade. In essence, today’s Luddites want us to smash the machines — but only when they aren’t actually machines.

But why?

Over the last several decades, workers around the world have been lifted out of poverty at an unprecedented rate, in part because of liberal trade. More still will likely rise in the decades to come if trade continues to open. To be sure, if these forces are left unchecked, we may also see greater displacement, inequality, wealth consolidation, and environmental degradation. The key then is not in scrapping the trade deals but in addressing each of these social ills as problems in themselves — just as we do when they arise from industrial modernization.

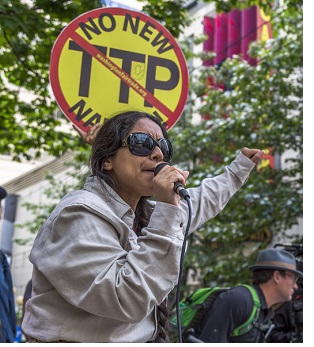

Take, for instance, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, or TPP. Those on the political left concerned about labor or the environment harbor a traditional wariness of liberal trade, and that tradition has many prominent adherents. Robert Reich has called the TPP "the worst trade deal you’ve never heard of." (Never mind that he assigned this epithet ten months before the text was made public.) Other luminaries ostensibly in Reich’s camp include Jeffrey Sachs, Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, and (now, it seems) Hillary Clinton, to name only a few.

Take, for instance, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, or TPP. Those on the political left concerned about labor or the environment harbor a traditional wariness of liberal trade, and that tradition has many prominent adherents. Robert Reich has called the TPP "the worst trade deal you’ve never heard of." (Never mind that he assigned this epithet ten months before the text was made public.) Other luminaries ostensibly in Reich’s camp include Jeffrey Sachs, Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, and (now, it seems) Hillary Clinton, to name only a few.

Meanwhile, in a recent break with longstanding tradition, the Republican Party has also turned against trade deals. The GOP nominee has prominently denounced most such deals to which the U.S. is party as "very bad." All mention of support for the TPP has been stripped from the party platform. And while many GOP elites still support the TPP, the party’s insurgent populist wing has made opposition to the trade pact a practical litmus test.

If everyone agrees the TPP is bad, maybe it is. Perhaps this is a machine worth smashing. Right?

Perhaps, but it’s doubtful. For one, the anti-TPP crowd cannot agree on why the deal is so bad. Some think it undermines regulation abroad. Others claim it undercuts domestic workers. And some claim its flaw lies in not expressly addressing climate change (although nearly the entire world recently adopted an ambitious and hard-fought agreement devoted exclusively to that issue). It’s alternately a good deal for the U.S. at the expense of foreign countries, and a raw deal for the U.S. for the benefit of other countries. This list of supposed vices is by no means exclusive. The inability of the anti-TPP choir to find the same key, let alone to sing the same song, is a strong indication that at least some of the critics must have missed the mark.

More likely than the notion that the TPP is uniquely bad is that it is actually no worse than any other of our trade deals, and significantly better in some ways compared to past ones, including with regard to labor standards and the express preservation of signatory countries’ power to regulate within their borders.

More likely than the notion that the TPP is uniquely bad is that it is actually no worse than any other of our trade deals, and significantly better in some ways compared to past ones, including with regard to labor standards and the express preservation of signatory countries’ power to regulate within their borders.

If that’s the case, then anti-TPP sentiment does little besides pit the interests of rich countries’ workers against those of poor countries’ workers. It would not be the first time in history that competing interests had divided labor against itself, although rarely do we hear such efforts described as "progressive."

In fact, the TPP is just another variable in the complex of influences that shape labor demand. Would-be reformers routinely propose redistributive or remedial policies to address fluctuations from such variables — even when the problems are as novel as the potential automation of over-the-road truck driving or the economic woes supposedly laid bare by Pokémon Go. The challenges born of globalization warrant the same approach.

Even Robert Reich ultimately concedes the point: "The problem isn’t trade itself. It’s a political-economic system that won’t cushion working people against trade’s downsides or share trade’s upsides." That’s precisely the point.

Former Senator George Mitchell, who has long been a champion of the economic benefits of globalization, occasionally invites crowds to consider how his home state of Maine was once the hub of the thriving wagon-wheel and carriage industry. Then came the automobile. Senator Mitchell asks his audiences to consider whether the good citizens of Maine should have fought against the automotive tide to preserve their traditional livelihood. The alternative was to ride the broader prosperity made possible by that vehicular innovation. Maine’s wagon-wheel preeminence is obviously long gone. Despite being thus dethroned, the citizens of Maine are significantly healthier, wealthier, and more gainfully employed than they were in the days of their wagon-wheel preeminence. The lesson is clear. History has made the right path plain and reduced the road not taken to a punchline.

Lest there be any confusion, no one is suggesting that pressures on labor demand aren’t real. The seriousness of the policy challenge posed by labor displacement cannot be overstated. And it goes beyond worker well-being; the debasement of labor undermines our shared conception of economic prosperity. Basic economic theory posits labor as fundamental to production. And even if you don’t buy the notion that all value derives from labor per se, it’s harder to say the same of the incentives and proprietary rights that spring from and justify our daily toil. We work to create value in exchange for a slice of the value.

Like it or not, globalization, like automation, is here to stay.

We simply have no economic experience with a world that is productive by modern standards but in which labor is marginal or even superfluous. The utopia where humans will someday expend their energies on arts and leisure or on machine-augmented academic pursuits is purely hypothetical. In the real here and now, we must address the effects of labor displacement, whether from automation or from globalization, through sound, thoughtful domestic policy and not through parochial, knee-jerk sloganeering.

Like it or not, globalization, like automation, is here to stay. The future of a more open (and mechanized) global marketplace is inevitable. But how we greet that future remains to be seen. Keen wonks have brandished a broad assortment of creative and progressive policy proposals for dealing with the ramifications of what lies ahead technologically. We need similarly thoughtful proposals to address the pressures brought about by an ever-smaller global marketplace for labor.

The Luddites are coming. And if we want to keep the machinery of the modern market running, we had better make sure they aren’t hungry.

____________________

Jesse Medlong is a Pacific Council member, lawyer, veteran, and member of the Truman Project Defense Council. Follow him on Twitter: @JCMedlong.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Pacific Council.