You are not alone if you have lost the plot line around what is happening in the U.S.-China relationship. This week alone marks another round of proposed tariffs, this time to the tune of some $200 billion, leaving many policymakers, politicians, and pundits scratching their head as to where we go next.

Admittedly, confusion in these circles has been the order of the day since the 2016 presidential election, when what was safe to bet on—both in terms of policy choices and acceptable political personalities—disappeared into the rear-view mirror. Want to understand what happened in the election? As with any big historical inflection point, the reasons are many. But front and center are Americans’ economic anxieties about the future in general and towards China specifically.

In the period immediately following World War II, every near peer economic power that today the United States competes with economically had been destroyed: Germany, Japan, China, all gone. The economic might the United States assembled in the years after this era, and the benefits that accrued to our middle class during this period, were aberrations.

If politicians and policymakers in the United States had worked as hard as their counterparts in Germany, Japan, and China in the decades since World War II, much of the economic insecurity Americans feel today could have been mitigated.

Economically, victory after World War II left the United States the unassailable strongman. Our manufacturing output amounted to more than half of the world’s total: more than half of anything that was manufactured anywhere in the world was made here. No surprise that this period is thought of as the golden era for a middle-class worker. When your economic competition is literally in rubble, you win simply by having available capacity.

The middle class that many in America remember today was the result of the historically unique tragedy of World War II. Most importantly, if the United States wanted to maintain the integrity of its middle class, it would have approached globalization and the means by which we invest in education, infrastructure, and innovation with much more attention, discipline, and focus than we did.

If politicians and policymakers in the United States had worked as hard as their counterparts in Germany, Japan, and China in the decades since World War II, much of the economic insecurity Americans feel today could have been mitigated.

When government cannot help its citizens navigate these moments, people turn to those who promise to burn it to the ground.

This is not to suggest economic pressures on the middle class would have gone away; rather, that most Americans would be in a better place, with a more educated populace, and a more elastic political system capable of thoughtful policymaking. It is also to reinforce a critical point: it is the conceptualization and coordination of how a society is to respond to these pressures that constitutes what good government is about.

When government cannot help its citizens navigate these moments, people turn to those who promise to burn it to the ground. After all, if government cannot help, then what is the point tolerating all the intrusions and excesses of any large institution that is supposed to be working on your behalf?

This same post-World War II period also laid the groundwork for many American multinationals who dominate the world’s economy today. Beyond the economic gains, the American culture, way of life, and political ideas were elevated to the global ideal—standards they richly deserved. American politics put forward a vision that government was empowered by the consent of its citizens, that personal freedom was an absolute necessity and that this freedom was integral for economic growth. American movies exported a vision of what it was like to live in America, admittedly with Hollywood’s own special spin. American-made products embodied the best version someone in the middle class anywhere around the world would ever aspire to own and enjoy.

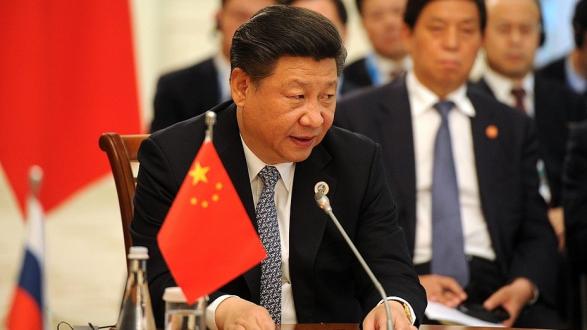

When we hear President Trump talk about how China is beating us at our own game, he is tapping into a pervasive sense that China’s policymakers have been nimbler, more astute, and more productive than our own.

Amid our current economic struggles, it is easy to lose sight that the world we live in is a world we created. When we hear President Trump talk about how China is beating us at our own game, he is tapping into a pervasive sense that China’s policymakers have been nimbler, more astute, and more productive than our own, and that our middle class has suffered as the result. As the 1980s and 1990s advanced, these decades would mark a moment when America’s political class demonstrated a spectacular lack of imagination and vision over how China’s entry to the world’s system of trade would impact American workers.

When America first embraced globalization, the country was economically secure. The years immediately following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War elevated the Washington model to a position of unquestioned primacy. In this moment, America adopted a generous position towards the world, and China in particular.

Ideas about globalization were deeply encoded with the belief that no country could forever resist American ideals. No matter how entrenched another country’s system of governance was in an opposing ideology, it would ultimately have to look like America’s. Consequently, no matter what a country’s founding ideology might be, it would ultimately bend towards a version that looked like America.

While trade with China created many benefits, it has also led to an era of economic insecurity for America’s middle class. This moment was not purely China’s—or globalization’s—fault.

Supporting ideas around how the United States would handle potentially harmful economic dislocations during this process of globalization were trivialized. Progressives emphasized the role of new high technology jobs and the service industries as ways to support any short-term economic pain. Pro-business conservatives, in an embrace of free market fundamentalism, confidently asserted that the invisible hand of the free market would see labor geographically and vocationally re-organize.

Both approaches badly missed the mark around how globalization would impact middle America. While trade with China created many benefits, it has also led to an era of economic insecurity for America’s middle class. This moment was not purely China’s—or globalization’s—fault. Rather, the economic insecurity of the American middle class today reflects long standing unaddressed issues around rising costs for healthcare, housing, education, and childcare.

If we were to take China’s economic metrics and project them onto a country or region we do not feel threatened by—say nearly any in Africa—we would applaud their success under both ideological and humanitarian grounds.

American fears about China are frustrations over how America’s political leaders have failed to craft a coherent vision for America’s economic future. Whatever gripes we may have with China’s leadership, no government in recent history has been as effective as China’s has been at lifting its people out of poverty. If we were to take China’s economic metrics and project them onto a country or region we do not feel threatened by—say nearly any in Africa—we would applaud their success under both ideological and humanitarian grounds. We would call their success a great good, rush to study it, and make it an object lesson for those in need. For the briefest of periods, China’s rise was greeted along similar lines.

Now that their success has diverged from our own, deep insecurities have presented themselves. While there are many reasons to distrust China, even to vigorously combat their regional and global ambitions, there are even more reasons to avoid blaming China. Not because China is above blame, but because the root cause of America’s current economic anxiety has less to do with any decision made in Beijing, and much more to do with those made—or not made—in Washington.

_____________________

Benjamin Shobert is a Pacific Council member and founder and managing director of the Rubicon Strategy Group.

This article is an excerpt from Shobert’s new book, Blaming China: It Might Feel Good but It Won’t Fix America’s Economy, published by Potomac Books.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Pacific Council.