Internet freedom around the world is continuing its steady decline. Today, two-thirds of all internet users (67%) live in countries where their government censors free speech, a number that’s growing year over year—expanding beyond typical authoritarian regimes and now even impinging on U.S. soil.

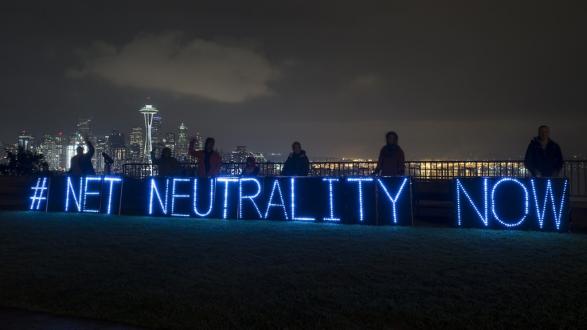

With the FCC’s repeal of net neutrality in America and the outcry among citizens who fear the stripping of their digital rights, this is a key moment for internet freedom. From legislation to technology to activism, it’s imperative to define and protect these rights. The impending battle stems far beyond net neutrality and it exceeds our country’s borders. This remains a global fight, one that should be a universal goal that we tackle together.

Back in 1948, at the end of the world wars, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), a milestone document drafted by representatives with differing legal and cultural backgrounds from all regions of the world. For the first time, the document laid forth fundamental human rights to be universally protected, including civil, cultural, economic, political, and social rights. Over time, the United Nations has expanded the law to encompass standards that protect women, children, people with disabilities, minorities, and other vulnerable groups, evolving the document alongside our ever-evolving society.

But one aspect that has never been included, mostly because it didn’t exist until more recently, is the incorporation of digital rights.

Let’s be clear: There is no such thing as “digital rights.” Digital rights, by definition, are basic human rights. Or at least they should be recognized that way. Back in 1948, not even the smartest of minds could have imagined the world we inhabit today—a landscape entirely reliant on the internet. The web is interwoven into our lives, providing an endless stream of information and connecting people in a way few could have envisaged. Without the internet, our lives would come to a grinding halt.

There is no such thing as “digital rights.” Digital rights, by definition, are basic human rights.

The way the world has evolved speaks to the importance of defining these rights. This should occur on a global level with input from all backgrounds and cultures, much like we saw back in 1948. After all, the internet is a world without borders or walls. It cares not about race, religion, or gender. It remains a fundamental tool in the fight for better governance, human rights, and transparency. And increasingly, online activism is showing real, tangible results in triggering change.

Yet governments around the world seek to extinguish these outlets, with social and communication apps being the primary targets. For example, during 2016 in Uganda, the government attempted to restrict internet freedom in the run-up to the presidential election, blocking social media platforms and communication services such as Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp.

In Cambodia, police arrested numerous people for their Facebook posts, including one about a border dispute with Vietnam. In Brazil, at least two bloggers were killed after reporting on local corruption. And in Saudi Arabia, a court sentenced an individual to 10 years in prison and 2,000 lashes for allegedly spreading atheism in his Twitter posts. Then, in Egypt, a photo-shopped Facebook image depicting President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi with Mickey Mouse ears resulted in a three-year prison term.

The volume of incidents like these remains alarming. There are reports, even, of people going to jail for merely “liking” posts that disagree with their government's political stance.

In the United States, we do not face such severe challenges. According to Freedom On The Net’s 2016 annual report, China remains the least free country with Syria, Iran, and Ethiopia close behind, while Estonia, Iceland, Canada, and the United States remain the freest.

But even the “free” countries are slipping. While in the United States you may not end up in jail for an anti-Trump tweet, we see laws being removed that protect our online communications, the regular promotion of false narratives, and a blatant disregard among our leaders for media exposing the truth. These may be minor compared to repressive countries — where Google, social media channels, and certain websites are blocked to control the narrative—but there’s no arguing that things are getting worse.

Let’s be honest: Internet freedom, a vital tool for democracy and free speech, remains a major thorn in the side of dictatorship-like regimes. These channels are a way for the people to rally, for citizens to be heard loud and clear above political rhetoric. Silencing those voices controls the narrative. Hence, internet freedom isn’t exactly a popular topic in many regimes.

Internet freedom, a vital tool for democracy and free speech, remains a major thorn in the side of dictatorship-like regimes.

As human beings of all races and from all walks of life, we need to work together towards regulations that protect our unified rights for open and free online communications. We need a framework that recognizes digital rights for what they are—human rights.

AT&T, for its part, suggested a “bill of rights” would be preferable to laws that come and go such as net neutrality. And to a degree, the company is right (albeit the bill it proposes would likely not be in favor of the people). The time is now to look deep into the future and deliver standardized laws for all—protecting future generations as well as our rights today.

But the creation of this policy should not be led by corporations or shameless politicians that require funding to help with re-election. Fronting the charge must be activist groups, independent advisors, and it should stem beyond domestic borders.

It’s time for our 1948 moment. The internet is now ingrained in our existence, and digital rights should officially become a part of our basic human rights. While this may not solve all our problems, and authoritarian countries will continue operating by censoring anyone who attempts to exercise these rights, it remains an unarguable step in the right direction. If we don’t make the topic a global priority soon, it could become too late.

____________________

David Gorodyansky is a Pacific Council member and CEO and Co-Founder of AnchorFree Inc.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Pacific Council.