California’s five-year drought was a serious wake-up call to the reality of water risk and the imperative to manage water resources more effectively. Around the globe we are seeing a similar awakening around water risks—be they floods, droughts, or water contamination.

The drought disrupted farmers’ harvests, companies’ operations, and households’ habits. Likewise, in places as far flung as India, Brazil, large swaths of Africa, and the U.S. Midwest, drought has influenced decisions and fortunes in recent years. Meanwhile, elsewhere around the globe, hurricanes and floods have literally obliterated fields, factories, and neighborhoods.

The immediacy of those risks has heightened the concern of another group: investment firms. Major investors are increasingly on the lookout for water risks in their portfolio companies or across industries in which they may be invested. For instance, a savvy investor may be wary of buying stock in companies whose operations need more water than is readily accessible, like a food company depending on crops from drought stricken areas, or in companies that might be liable for tainting local water supplies—as has been alleged of oil and gas extraction companies, including those doing business in California.

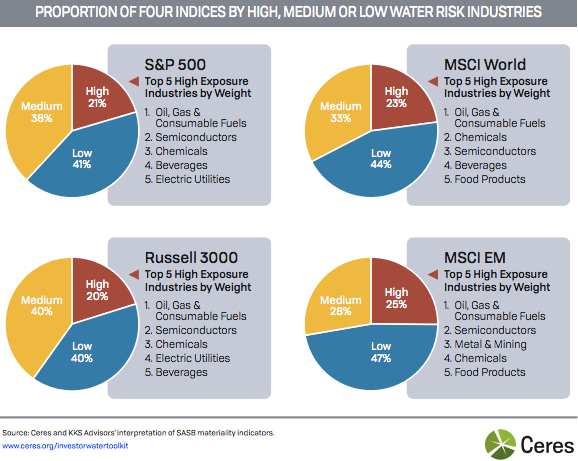

At least 50 percent of the stocks listed in each of the four major stock indices are in industries that face medium to high water risk. That is akin to saying roughly half the industries in our economy face significant water risk.

This growing concern about water—a resource that used to be taken for granted—is reasonable. For three years running, the World Economic Forum has listed water-supply crises as one of the top global risks. A recent study by Ceres of the four major stock indices found that at least 50 percent of the stocks listed in each of them are in industries that face medium to high water risk.

That 50 percent finding alone should be a wake-up call. It is akin to saying roughly half the industries in our economy face significant water risk.

Driving through California’s Central Valley, you can often see firsthand water’s influence on the economy. In 2015 and 2016, there were miles of fallowed fields when farmers were short of water for irrigation. Then, in 2017, many of those fields were green and planted again. But then the heavy rainfall and floods of winter 2017 had their own impact on the economy, causing $1 billion in damage.

To help investors understand water risk, evaluate that risk, and make water-aware investment decisions, Ceres this week released an Investor Water Toolkit, a comprehensive online platform that describes the analytical filters and decision-making steps investors should use to gauge that risk and minimize exposure to it.

Water-risk drivers include weather and climate change, water pollution, floods, growing competition for water, and reputational risk. The risks can translate to dollars lost.

Water-risk drivers include weather and climate change, water pollution, floods, growing competition for water, and reputational risk if consumers decide a company is not sharing or adequately stewarding water supplies.

The risks can translate to dollars lost. For instance, BHP and Vale face a $48 billion fine from claims filed after a mine wastewater dam in Brazil burst in November 2015, causing destruction of local communities, loss of life, flooding, and contaminating water supplies.

As you can see below, certain industries hold more water risk than others. Oil and gas fuels, food and agriculture, semiconductor manufacturing, and beverages are high on the risk scale—and these industries are all significant in California’s economy.

These industries have water-intensive operations that are likely to affect the quality and quantity of local water resources, the Toolkit indicated. Consequently, companies in these industries can face strategic, operational, regulatory, and reputational risks related to their water needs and water use.

The Toolkit also looks at geographical risks through heat maps—the kind of heat maps Californians became accustomed to during our drought, when a big swath of state maps changed from orange to red to maroon as the drought worsened.

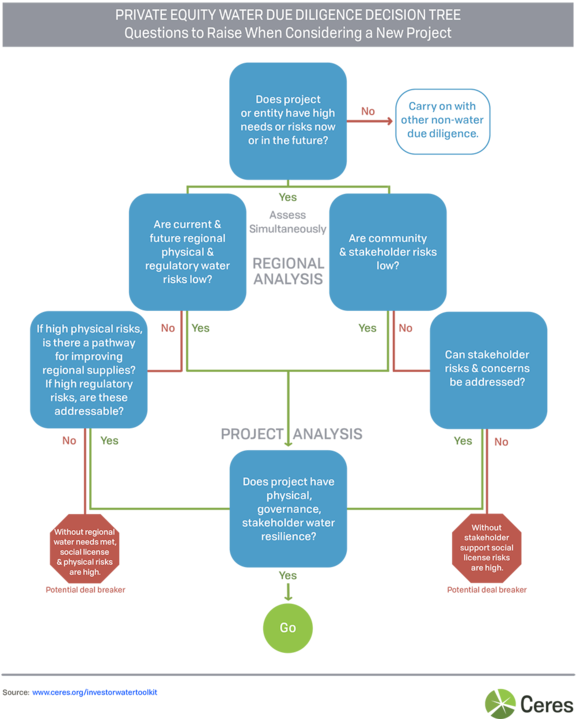

And the Toolkit provides a private-equity decision tree to lead investors and others through a process of detailed analysis to figure out if a risk is significant and how a company or institution considering a project should respond to that risk. Private equity investors find that the biggest risks can come from poor regional management of water.

In recent years, we’ve seen companies use heat maps and identify California as an area of high water risk. As more companies and investors scrutinize water risk and become savvy about how to evaluate and respond to it, California will always be under the spotlight because of our climate, weather patterns, and recent history of drought.

However, if companies doing business there are careful stewards of water, and the state implements smart policies around, say, water conservation and groundwater usage, then investors will retain confidence that California water agencies, businesses, and people know how to wisely share and care for this resource.

That’s what investors will be looking for when they assess a company’s value and growth potential. They want to know that future projections of water needs for a company and its region can be met and wisely managed. If we collectively work on good water governance in California and shared responsibility for this precious resource, we’ll earn their confidence—and business.

_______________________

Kirsten James oversees the California policy program at Ceres, a nonprofit sustainability advocacy organization. She recently spoke at our inaugural Water Conference.

This article was originally published on Water Deeply.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Pacific Council or Water Deeply.