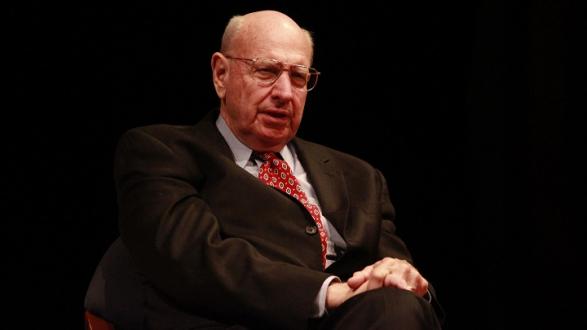

What is the most pressing global issue that is not receiving enough attention? How do we play hardball with Putin and still make progress on Iran and other issues where we actually need Russia's cooperation? Event Envoy Nina Hachigian, a long-time Pacific Council member and U.S. Ambassador to ASEAN, pressed for answers to these questions and more in her interview with Ambassador Thomas R. Pickering last week.

Review the full one-on-one interview below to learn more about this senior diplomat's take on U.S. vital interests and where our foreign policy is falling short.

____________________

Ambassador Hachigian: I’ll begin with the Pacific Council “hallmark question”: What is the most pressing global issue that is not receiving enough attention?

Ambassador Pickering: That’s an interesting question. There are a number of issues on the agenda not receiving enough attention right now. Global warming is an important one. I think the question of how to bring some of the new multilateral trade negotiations successfully to conclusion is another. Can we find a way to pluralize them? In other words, do we have trade strategy or are we just seizing opportunities? With the failure of Doha, we have lost a trade strategy in my opinion. Instead we have a series of once-off opportunities and over time this produces real anomalies.

We need to be alert and aware of the fact that unexpected or poorly predicted health crises will strike from time to time, given our mobile society and lack of immunity.

Ebola has also raised the important issue of international health. We’ve done very well with the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). But, is there an opportunity to pluralize the PEPFAR structure and institutional arrangements? We need to be alert and aware of the fact that unexpected or poorly predicted health crises will strike from time to time, given our mobile society and lack of immunity.

Finally, for a long time I have felt that we need a new, coherent effort on agricultural improvement. There may be real opportunities in GMOs, but there are also concerns, which are in my view somewhat fanatical. There is also an unwillingness to look at the need to provide a mechanism to correct for the fact that subsistence farmers used to rely on their existing crops for next year’s seed and now they have to buy GMO seed. Perhaps we could find banking or loan arrangements that bridge this gap and provide capacity. I think that for big countries like India we should look at systematic ways of overcoming some of the big challenges subsistence farmers face like access to good inputs, post-harvest food losses, marketing, and securing food processing arrangements. One of my suggestions is to see if we can work out partnerships that bring together large numbers of Indian subsistence farmers in a cooperative arrangement and coordinated effort to deal with the front- and back-end agricultural challenges. I haven’t worked out the economics yet, but maybe we could try this in some parts of India with a local partner.

Hachigian: While we are on India, what are some of your impressions of Modi and what he’s done?

Pickering: Modi has done pretty well. He’s made it quite clear to everybody that he wants to improve the Indian economic conditions and that he’s looking for foreign investors. His strategy will be to find a few large investors he can work with, rather than to jump into institutional arrangements that he then has to push these investors into. I think this is quite interesting and we’ll have to see whether it works. I think that he has an opportunity, given his new focus and concentration on Asia, to make India a real player there. The question will be how can he improve relations with China and whether the Chinese are prepared to take a chance with him.

Hachigian: You explained during the program that hardball was the only game Putin understands. So how do we play hardball, and still make progress on Iran and other issues where we actually need Russia’s cooperation?

Pickering: The good news is we are actually making progress with Russia on Iran. The problem is preventing the issue of Ukraine from infecting this. How do we begin to discuss a solution to the Ukrainian problem with Putin? Poroshenko is trying, but I think he may have gone too far in some ways and not far enough in others. He may have gone too far by institutionalizing an autonomous set of arrangements for the eastern oblasts. But, then he didn’t go far enough with defining how those arrangements would work and be more broadly applied to Ukraine as a whole. We also need to start discussing with the EU, Russia and other players how to address Ukrainian economic difficulties.

The good news is we are actually making progress with Russia on Iran. The problem is preventing the issue of Ukraine from infecting this.

We need more than just large dollops of money in Ukraine. We also need to hold them to some kind of reform plan and identify potential areas of investment. Boeing has done a lot of work in Russia on this. They have brought in aviation design engineers and there are around 150 Ukrainians working on this in Kiev. Kiev has technologically capable people and relatively low labor wage rates. So, perhaps knowledge industry expansion is worth pursuing.

Hachigian: What do you think America should be focused on with regards to security in Asia?

Pickering: I think we could begin to discuss options with the Chinese to ameliorate the situation in the South China Sea. We could start by picking one area of territorial dispute and attempt, through negotiations and/or arbitration, to resolve the issue. We should also make it clear to them that we’re prepared to continue to exercise our high seas rights of innocent passage. We should clarify that we don’t intend to enter their territorial waters or air space and that the kinds of vessels we’ve been sending have essentially been unarmed vessels. We could begin with this, making sure not to get ourselves into a position where we can’t send armed vessels. We need to work to build up our relationship by putting things on the table that are less contentious. From there, we could expand to see if in disputed areas they could freeze activities, or more importantly, whether they would be open to dividing ownership by 50 percent, in cases where the claims are solid on both side. Overall, I think we need to focus on securing smaller, piecemeal settlements as a way of starting a larger process.

Hachigian: “Maintaining credibility” in a given region is often cited as a reason for U.S. international action. What you think of this argument?

Pickering: I think that the vaguer the interest is, the less reliable the credibility argument is. The credibility argument is a second order argument to a first order justification of interest.Truman said our only “vital” interests are survival and prosperity. I suppose in some ways this also extends to the survival, if not the prosperity, of our allies. Everything we’ve been spending all this blood and money on are really just secondary, high priority interests. People will call anything a vital interest to justify doing it. We don’t currently have a grand strategy with regards to U.S. interests. Maybe we need one. However, we would need to recognize that for those interests designated as secondary, high priority there would likely be limits. I’ve been asked whether we’d go to war to stop Iran from getting a nuclear weapon. I said we’ve already gone to war to stop a country from getting a nuclear weapon—Iraq. The only problem was they didn’t have one [laughs].

We don’t currently have a grand strategy with regards to U.S. interests. Maybe we need one.

It would be useful to, for example with ISIL, place issues on a scale of priorities. In the end, would our vital interests be threatened if ISIL survives somewhere in some way? Personally, I don’t think so. I don’t even think our vital interests are threatened by part of Al Qaeda surviving somewhere. Of course I don’t want 3,000 people killed in a single shot, but I have to say I don’t think Al Qaeda’s eradication is a vital interest. It is, however, a huge domestic political issue and very important. Were we to know about 9/11 in advance, we would certainly need to take serious steps to stop the devastating events of that day.

I think it’s worth thinking about questions like: what was there to justify going into Iraq in 2003? I don’t see the vital interest there. I think particularly large scale military activities have to be considered in terms of palpable self-defense. Perhaps this could extend to preventative measures based on the strength of the self-defense argument. Resorting to military force for any other reason should be in the highly questionable category. I wouldn’t say that it should be entirely ruled out, but when you have a choice, the bias should be against use of military force.

Additionally, in some of those cases we might want to go to the UNSC before doing anything. This would help to build this step into our system of thinking. There are some who would say you really just need to go to Congress. But, in the last three to four cases like this, Congress has come down on the wrong side. In the First Gulf War they almost said no and in the Second Gulf War they didn’t say no.

____________________

Ambassador Nina Hachigian is a Pacific Council member and the U.S. Ambassador to ASEAN.