In this 70th anniversary year of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, a historical perspective on the country’s evolution over the decades may be instructive. The rise of China is arguably the biggest foreign policy challenge for the global community today. This is because what China has turned into in recent years is a far cry from the optimistic vision of the country’s future when it embarked on economic reforms under Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s after the excesses of the Maoist era.

Back then, the unspoken hope was that Deng’s reforms would eventually pave the way for an economic and political liberalization at home and China’s peaceful integration into the liberal capitalist world order. Under this hopeful assumption, the global community including the United States, the European Union, and China’s neighbors in the Asia-Pacific effectively adopted the following modus operandi vis-à-vis China: do not treat China as an enemy but rather encourage its economic development and opening to the outside world.

With this blessing from the global community, China has achieved spectacular successes since then, to the point where it is now considered a matter of time before it officially overtakes the United States as the biggest economy in the world. However, China’s successes have not been accompanied by changes pointing to liberalization at home or peaceful integration into the liberal capitalist world order.

Beijing’s recent footprints paint a worrisome picture of a rising hegemonic power determined to subvert the norms of the liberal capitalist world order.

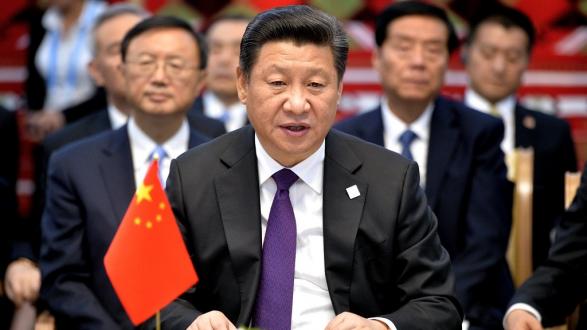

To the contrary, Beijing’s recent footprints paint a worrisome picture of a rising hegemonic power determined to subvert the norms of the liberal capitalist world order: its territorial expansionism in South China Sea that defies international law; its military buildup with a rising capability to challenge U.S. naval supremacy in the Western Pacific; and its state capitalism with an industrial policy and mercantilist practices that advantage Chinese firms over foreign ones. What makes all these developments even more worrisome is the increasingly repressive nature of China’s polity today: under Xi Jinping, China has returned to a cult of personality reminiscent of the Maoist era.

Of Beijing’s recent footprints, what worries its Asian neighbors the most is its expansionism in waters including the South China Sea. Indeed, Beijing’s maritime expansionism has led its neighbors to wonder if it has embarked on an all-out campaign for regional and even global domination as the rising new hegemonic power.

It must be pointed out that Beijing views its expansionism in different terms, namely, through the lens of its own interpretation of world history. The Chinese know their history. They know that China is one of the oldest and leading civilizations in the world that for centuries had been the largest economy in the world. In their eyes, therefore, China is a victim of modern Western and Japanese imperialism which, starting with the Opium Wars of mid-19th century, inflicted on China what is known as its “century of humiliation.”

While the global community of nations must be sensitive to China’s memory of its “century of humiliation,” they must, at the same time, make it clear that they no longer view China as a victim of modern history but rather as a rising superpower with a real power to inflict harm on other nations.

In Beijing’s eyes, China thus has the moral high ground vis-à-vis the West and Japan: China’s history since the mid-19th century is a righteous struggle to regain its rightful place under the sun. Imbued with this view of history, China thus seems to justify whatever expansionist policy it pursues overseas as entirely in its legitimate self-defense.

The global community of nations must point out to China the fallacy of this victim mentality. While they must be sensitive to China’s memory of its “century of humiliation,” they must, at the same time, make it clear that they no longer view China as a victim of modern history but rather as a rising superpower with a real power to inflict harm on other nations. They must speak with one voice if they are to effectively counter Beijing’s expansionism: they must not let Beijing play “divide and conquer” by playing them off one against another.

In the South China Sea, the West and China’s Indo-Pacific neighbors need to figure out how to jointly counter Beijing’s low-intensity subversive tactics, which are reminiscent of the methods used by Russia in Crimea. A good way to start would be enhancing joint military exercises and other forms of multilateral security cooperation between the United States and China’s Indo-Pacific neighbors.

It is high time for China to understand that being expansionist and hegemonic will thwart its economic advancement.

In the economic arena, the United States, EU, and other stakeholders in the global capitalist system such as Japan and South Korea need to form a shared policy response against China’s mercantilist state capitalism. This may not be easy given that China is now the biggest trading partner for many of them, but efforts to find a set of common interests around which to form a united stand against China should be worthwhile. Such interests could include IP protection, cyber security, fighting corruption, and boosting transparency.

In conclusion, the clear message that China gets from the global community should be that it must stop playing victim and start acting like a responsible, mature member of the global community. Beijing must be made to realize that the world has changed since the glory days of the Chinese Empire. There are new realities of the modern world system, such as international law, the rule of law, democracy, and human rights, which China cannot simply ignore.

China must realize that its old imperial ways such as the traditional foreign policy paradigm of tributary relations no longer work today. In fact, Beijing needs to see that it can be a dominant economic power without being territorially expansionist and hegemonic. Indeed, it is high time for China to understand that being expansionist and hegemonic will thwart its economic advancement.

____________________

Jongsoo Lee is Senior Managing Director at Brock Securities and Center Associate at Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Harvard University. He is also an Adjunct Fellow at the Hawaii-based Pacific Forum. The opinions expressed in this essay are solely his own. He can be followed on Twitter at @jameslee004.

A version of this article was originally published by the Pacific Forum.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Pacific Council.