The year 2007, according to traditional astrology, was the Year of the Golden Pig. It was believed that good fortune would come to families who gave birth during this auspicious time. Regardless of the role that astrology may have played, Mongolia’s annual birth rate grew from 50,000 in 2007 to nearly 90,000 in 2014, and Mongolia today is one of the youngest nations in the world, with young people age 14–34 comprising 35 percent of the population.

So, what does this mean? First, it means there is a pressing need for more kindergartens, more schools, and more jobs, demands that the country is striving to meet. But more importantly, this cohort of young people will have a dominant role in charting Mongolia’s course through the perilous social and economic challenges it faces today, including the nation’s high levels of corruption.

The Asia Foundation’s annual Survey on Perceptions and Knowledge of Corruption shows clear cause for concern about the experiences shaping the outlook of Mongolia's critical youth demographic.

The Asia Foundation’s annual Survey on Perceptions and Knowledge of Corruption (SPEAK) shows clear cause for concern about the experiences shaping the outlook of this critical youth demographic. The research shows that most of Mongolia’s petty bribery takes place in public services such as health and education. In a multiyear average, at least a quarter of those who said they had paid a bribe reported that it was to teachers.

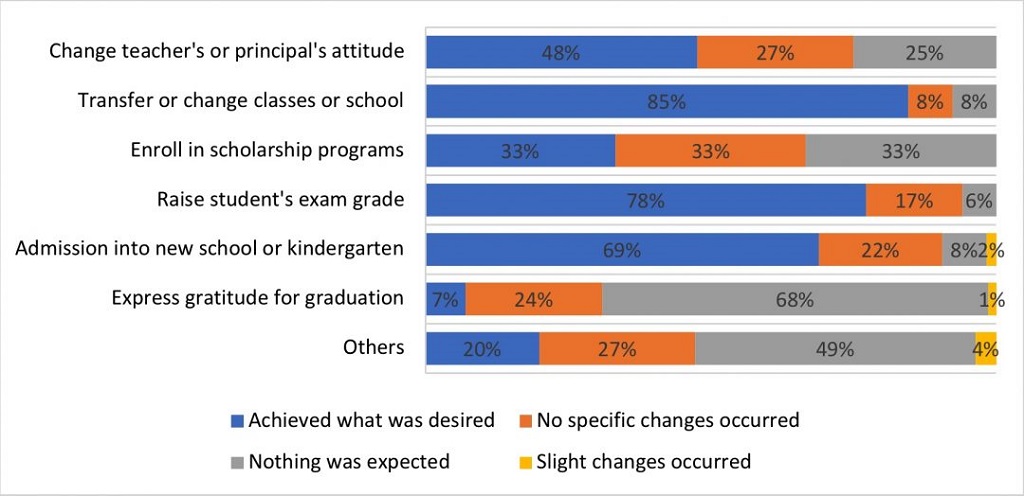

The hard fact is that many young people in Mongolia are growing up and being educated in an environment of corrupt and unethical behavior. The Foundation’s 2016 survey Transparency, Ethics, and Corruption in the Education Sector found that nearly 40 percent of parents had given small bribes to teachers in return for favors such as better treatment, preferred admission to better schools or classes, and higher grades. Alarmingly, when parents were asked about the results of these payments, 78 percent of those who wanted higher grades for their children said the payment or gift had achieved the desired result (figure 1).

Fig. 1: Result of giving gifts or money, by purpose of the gift

When asked if this culture of bribery should be tolerated in the future, 92 percent of parents said no. But when asked if the situation was likely to change, they were pessimistic: 40 percent predicted it would worsen, and 30 percent said it would remain the same.

Low teacher salaries and limited funding for public schools are often cited as the cause of or excuse for this corruption and for not aggressively tackling the problem. But the cost of corruption is more than just the money paid by parents: it’s exposing young people to these practices, which affects their ethical worldview. It is the students who often handle the money in these transactions—they know the purpose of these payments and that they are benefiting from them.

Students discuss corruption

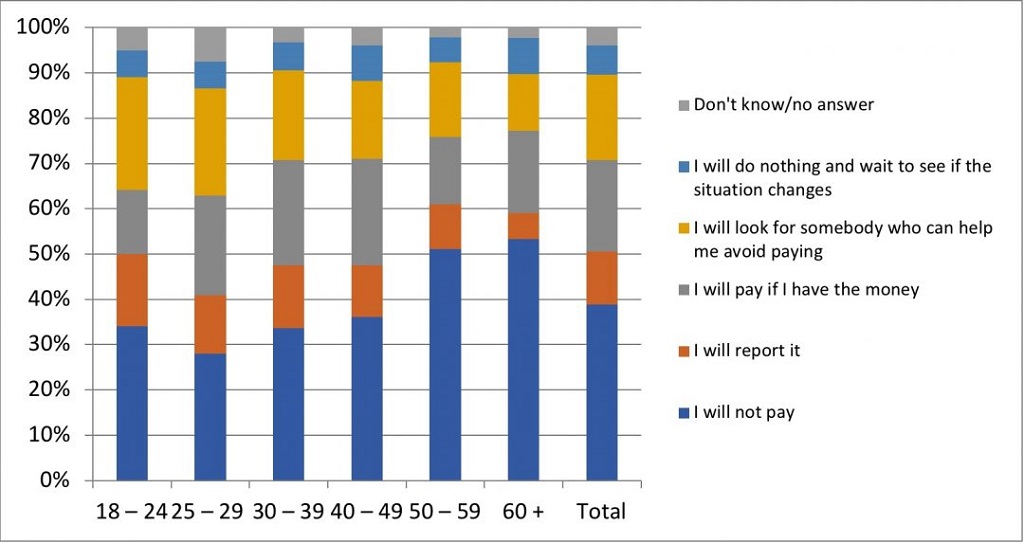

It is not difficult to imagine how young people raised in such an environment might act when they make decisions relating to corruption in the future. According to last year’s SPEAK survey, zero tolerance of corruption is considerably less common among youth than among older age groups. For example, only 28 percent of those age 25–29 say they would not pay a bribe, compared to 51 percent of those 50–59 and 53 percent of those over 60 (figure 2).

Fig. 2: If you face a situation in which you are directly asked for a bribe by a public or private official, what is your most likely action? (March 2017, by age group)

So, how can we prevent our children and young adults from succumbing to this culture of corruption? What strategy or methodology should we follow to educate youth? Can we, and they, change the course of development towards a fair and just society in 10 or 20 years? These are the critical questions that Mongolian educational institutions, civil society organizations, and government agencies are trying to answer. The Asia Foundation’s Mongolia office has been engaged in anticorruption activities in the education sector since 2010, and with generous support from the Canadian government we launched a wider intervention campaign for secondary schools and colleges in 2016 as part of our 10-year-old governance and anticorruption program.

Under this initiative, several NGOs and local education authorities are conducting trainings and public-awareness events for hundreds of teachers and thousands of students at 130-plus public secondary schools and 60 colleges and universities in Mongolia’s capital city, Ulaanbaatar. At the same time, local NGOs are helping school administrations improve the transparency and accountability of their finances through active school-reform projects.

Despite years of work, clear signs of improvement in the corrupt culture of the education sector are yet to be seen. But educators and activists say these anticorruption efforts must continue to ensure long-term success.

Despite years of work, clear signs of improvement in the corrupt culture of the education sector are yet to be seen. But educators and activists say these anticorruption efforts must continue to ensure long-term success.

The Asia Foundation’s Survey on Perception and Knowledge of Corruption (SPEAK) is conducted in partnership with Sant Maral Foundation. The survey, which uses random sampling methodology, has been conducted for the last 10 years. The Foundation’s 2016 survey Transparency, Ethics, and Corruption in the Education Sector was conducted in partnership with a local survey firm Statistical Institute for Consulting and Analysis.

_____________________

Bayanmunkh Ariunbold is a governance project manager for the Asia Foundation in Mongolia.

This article was originally published by the Asia Foundation.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Asia Foundation or the Pacific Council.