Earlier this month, I had the distinct honor of meeting former President Mohamed Nasheed, Maldives’ first democratically elected president, Amnesty International’s former Prisoner of Conscience, the UN’s Champion of the Earth, and one of Newsweek’s World’s 10 Best Leaders. He served as president from 2008-2012.

Fondly known as “Anni” across the Indian Ocean archipelago-state of the Maldives, President Nasheed is widely recognized for his tireless fight for democracy, individual freedom, human rights, and climate action. All the while, he has remained one of South Asia’s most popular and charismatic leaders, intellectuals, reformers, and political strategists. His solid, grassroot-level, domestic popular support base is unmatched compared to most world leaders.

President Nasheed took on powerful, well-entrenched authoritarian regimes and helped to bring sweeping social and political change in difficult, constricted environments of fear and uncertainty, as recently as last year.

In his tumultuous career as a politician, journalist, and activist, there is little that Nasheed has not experienced. He has been imprisoned repeatedly, banished, exiled, tortured, and, in his own account, made to eat food with crushed glass. He has been shot at and asked to confess to committing terrorist crimes that he did not commit.

While I was recently in the Maldives, President Nasheed had just returned to the Maldives after a multi-year exile. He had recently announced that he would be contesting for a parliamentary seat in the upcoming elections in Malé. It was a unique moment to ask one of South Asia's top leaders about his thoughts on climate action, democracy, and electoral priorities, and to learn more about his life as an activist and politician over the last three decades. I reached out to President Nasheed's office for an in-person interview and was fortunate to have been granted some time given his busy, ongoing political campaign schedule.

We met at his residence in the capital-island of Malé, and what ensued was an enriching, hour-long conversation on democracy, climate change, and his inspiring, life-long work as an activist and politician.

Here is an excerpt of my conversation with President Nasheed.

_______________________

Nishtha Mishra: President, you first started to fight for fundamental rights and freedom as a young 22-year-old in Malé. Your journey has been marked by several notable achievements, but also by a great deal of strife and struggle. How did it all start for you?

President Mohamed Nasheed: Many, many Maldivian families have similar pasts and histories. My father, great-grandfather, and his father had all been tortured and banished for political reasons. They spent so much of their lives in banishment in far flung islands. For us, it all started with conversations during family lunches and dinners centered around these kind of stories. We grew up on these stories. Human rights and democracy meant a lot.

My father was relatively fortunate. He was arrested, then in jail for five years. After he was released, he became a trader. Our whole family was a merchant family. With the growing tourism industry in the Maldives, our family was a little prosperous. We were relatively luckier. We had some old money too, but after every two generations, the government would confiscate all the money and land that we had.

Our grandparents would start again, and after a generation, we would move up again. We were fortunate to get an education abroad. Many Maldivians do. But usually, it comes through a government scholarship. And it is difficult for families like ours to get those scholarships. So our parents worked very hard to give us an education. We all went to school and university in England because of that.

"There are many countries that have come to understand that they must find better and more sustainable development strategies. The United States is a different story. Even if the federal government doesn’t support certain policies, it is fine because each of the states have their own policies."

Mohamed Nasheed

Soon after university, I came home and started working for a small journal in Malé. At the time, India had aborted a coup in Malé. I remember that I had gone to India with President Gayoom in 1989 as a journalist. Rajiv Gandhi was the prime minister at that time. We were moving towards a parliamentary election in the Maldives. I was only 22.

At first, President Gayoom told people to freely share their views. So we did, but they didn’t like what we wrote. They arrested the whole editorial board. They practically arrested the whole of our generation that evening… all 270 of us. That night, they also deregistered the magazine. In the morning, Ibu Solih (the current president of the Maldives) escaped.

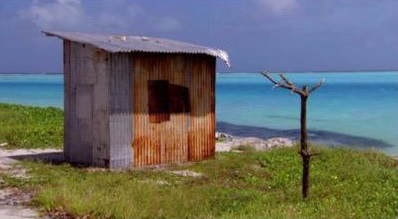

We happened to be in a room in our house. I was under house arrest even then for having given an interview. Then they came to arrest all of us. They wanted me to confess to a whole lot of things that I didn’t do or know about: that I was concealing a conspiracy to bomb the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) Summit, and that I part of a plot to overthrow President Gayoom. They took me under solitary confinement in a corrugated, iron cell and interrogated me, but I didn’t want to confess.

So I was jailed for three years. Then I got out and kept writing, and they arrested me again. I was tortured very heavily. Getting arrested and writing; this was the way of things. Then in 1999, I thought that if I contested for a seat in the parliament, I would be safer. That time Malé was electing two Members of Parliament (MPs). I am from Malé, so I contested from there.

"The Maldives is still in a precarious situation. We have seen with the previous government what can happen if things start going wrong."

Mohamed Nasheed

I won against President Gayoom’s ministers. I was in parliament for one and a half years, but was arrested again. So, my theory about being safe from arrests as an MP proved wrong. In between those arrests, I got married. I had my first born in 1997. After having been arrested as an MP, I was also banished, and then brought back to Malé. The conditions in Malé’s prison were very bad. Torture was endemic, there were riots, and people were dying.

I was eventually able to escape to Sri Lanka. We decided to form a party in exile, and registered at the Colombo post office. It turns out that Colombo wasn’t the safest place either; I was chased in my car and shot at, but was fortunately unharmed. So I moved to England and then India and agitated from there.

After a while, I decided to return to Malé and start the party. The momentum grew over time and we won our first election in the Maldives in 2008. I was truly fortunate to have won those elections. Halfway through, however, we had a mutiny. We were not able to really flush out the dictatorship. We have spent the last seven years trying to come back again.

You are currently running for a parliamentary seat from Malé this summer. What would you say is your top election priority? Also, why are you contesting?

Nasheed: I am running because I was not able to contest for a seat in the last presidential election. I fully support my friend, the current president. We grew up together, worked at a newspaper together, went to school together. We did everything together. He had been banished just as I was. But I want to be in the parliament, too. I do not want to give up. I do not feel that I am old. I can be in politics and serve the people still.

We have brought a coalition government, but we still do not have the constitutional legal framework to really maintain it. In Sri Lanka, they did that first; they fixed it constitutionally. We do not have that. The Maldives is still in a precarious situation. We have seen with the previous government what can happen if things start going wrong. Someone should be in the parliament. There is a lot of work that needs to be done. We need another fair election.

How did you deal with your painfully difficult and solitary experiences as a prisoner?

Nasheed: I focused on one day at a time. A day would go by. Then, a week. Then, a month. Then, a year. You only really start counting after a month. It is all dark so you cannot see outside. There is no sunlight and no windows. I was able to take a picture of my cell later when I was president.

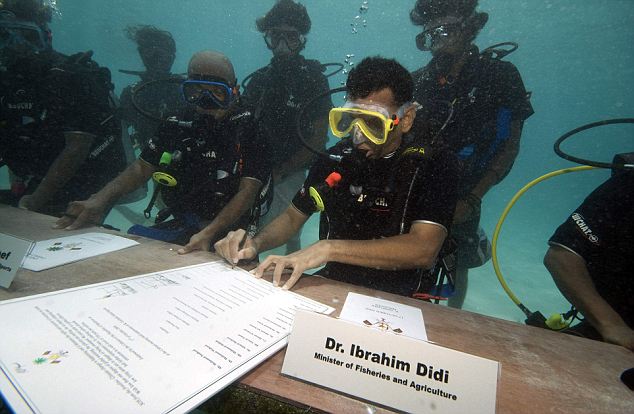

When it comes to climate change, the distinct efforts that you made to highlight the problem of rising sea levels as president is something which still blazes clearly in people’s minds. I am referring, of course, to the time when you held the world’s first underwater cabinet meeting, and signed a document asking all countries to reduce their emissions ahead of a UN climate change conference in Copenhagen. Where are we now with respect to climate change action? Realistically, what are you expecting in global fora?

Nasheed: In 2009, when I went to Copenhagen 19, India could not agree to the 1.5 degrees limit. A few years later, India was advocating for the 1.5-degree limit. The Indian negotiator at the time pointed out that they are the biggest island nation. India has as many islands as in the Maldives. In addition, India has more coastline, more mangroves, more reefs, and more low-lying areas.

There are many countries that have come to understand that they must find better and more sustainable development strategies.

The United States is a different story. Even if the federal government doesn’t support certain policies, it is fine because each of the states have their own policies. For example, California, with one of the largest regional economies in the world, has decided to go carbon neutral.

"We need to make better use of existing technology. We also need to start using nature itself as an infrastructure measure. Bio adaptation is the way."

Mohamed Nasheed

Today, even if you want to invest in coal, you cannot because no one is interested. As a case in point, recently in a power bid in India, the coal bid was more expensive than the renewable energy bid on an open tender. Solar is now cheaper.

So where are we now? I am hopeful. I am hopeful of us finding a new, low carbon strategy.

What are the next steps for the Maldives when it comes to dealing with climate change?

Nasheed: Adaptation, not mitigation, is the path for us. As it stands, my view on adaptation is that we are doing it all wrong. The thing we must understand is that we cannot stop nature. We must find softer, bio-adaptation measures instead. For example, we could grow a reef. I have been working with Sir Richard Branson and a big Indian construction company, which has worked extensively in India, Canada, and Africa, in this direction. My plan is to try to do a reef construction project where you can have a water breaker, and then a reef and a mangrove on top of it. That would have an estimated cost of about $40 per meter. What we currently do in the Maldives is costing us $8,000 per meter.

We should also think about genetic modification of polyps and having more resilient coral. And instead of reclaiming lands, as we have increasingly been doing in the Maldives, we should think of floating islands. We need to make better use of existing technology. We also need to start using nature itself as an infrastructure measure. Bio adaptation is the way.

There seems to be a lot of disenchantment around the world about the effectiveness of democracies in addressing people’s basic needs. Some of the disadvantages of being a democracy have really started to stand out. As the Maldives’ first democratically elected leader, you have done a lot to bring democracy in your own country. Do you think that democracy still works?

Nasheed: Well, it is like how Winston Churchill once said: it is very bad, but it is still the best that we have got. Here in the Maldives, we have not been a fully democratic country. My children have not seen it. So we are not exhausted with democracy. We still think that it is the best thing. Democratic freedom is very new to us. We are just becoming a state in which people think that it is wrong to torture people in jail. We are the first generation to think that people should not be trapped in chains.

"I do not subscribe to the view that democracy is not working. As leaders, we do what we can. But finally, it is up to the people to do their bit."

Mohamed Nasheed

I do not subscribe to the view that democracy is not working. Yes, we have seen some populist leaders coming up. But look at the elections in South Asia: Sri Lanka, Malaysia, now in the Maldives, and surprisingly, even in Pakistan. Prime Minister Imran Khan evidently has backing from all kinds of places, but he is still a different person. He is different from the leaders we have previously seen in Pakistan. There is a change.

As leaders, we do what we can. But finally, it is up to the people to do their bit. At the end, we can only do so much. And, of course, it is not just me. Until recently, everyone was so suppressed and afraid to do anything.

How would you characterize the place of the Maldives in the world, and within South Asia?

Nasheed: We are situated in a very geostrategic place. More than 80 percent of the world’s oil trade goes through the Maldives. We have three international channels. Our place is so strategic that we have to be very mindful.

"Our foreign policy is very simple: find a friend, be good to the friend, and do not play one friend off another."

Mohamed Nasheed

Our foreign policy is very simple: find a friend, be good to the friend, and do not play one friend off another. I think our best relationship is with India. We have been next to India for about 7,000 years and India has never conquered us or even wanted to occupy us. India wants to be friends with the Maldives, which is very good news for us. Ever since India opened up its economy, India has been growing rapidly. I hope that it will take its neighbors along with it.

China is an issue, however. Debt trap is an issue. Our fear is that we might be left out or dished out to someone else. We have to make it clear to strategists that we are important.

_______________________

Nishtha Mishra is a member of Pacific Council on International Policy. She has previously worked as an economic policy researcher at research organizations, and international development institutions in New Delhi, Dar-es-Salaam, San Francisco and Los Angeles..

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Pacific Council.